100 YEARS OF WHACKING THE MUSIC MELON

(April 2, 2021)

100 years ago this month, songwriters in the United States received their first-ever royalties for the public performance of their works, as the Directors of the American Society of Composers, Authors, and Publishers inaugurated a quarterly ritual that Variety would dub “whacking the music melon.” [N.B.: The title of this post is not a double entendre.] It was the start of a revolution not just in the business of American popular music, but in its sound as well. ASCAP distributions were the mother’s milk that nurtured the Great American Songbook.

Over the preceding three decades, the popular music business—centered on New York’s Tin Pan Alley—had thrived with a business model that treated public performances as a cost item, not a source of revenue. Revenue came from the sale of printed sheet music; the target consumers were modestly skilled home musicians, often self-taught, who played the parlor piano and sang barbershop harmonies for their own amusement. Even the best Tin Pan Alley songs were harmonically simple, easy to learn and remember, and required no great vocal or instrumental sophistication to perform satisfactorily. Songs which readily lent themselves to social singing, whether sober or drunken, were the most durable.

In a world without radio, television, or other mass media, Tin Pan Alley relied on public performances to advertise its wares. “Plugs,” in Tin Pan Alley’s argot, were simply public performances of a song, whether by sots in a beer garden, ringers planted in a theater balcony, well-coached demonstrators in a department store, or by hurdy gurdy men on the street. The most coveted plugs were professional performances by popular vaudeville stars who might take a song on the road and give it national exposure. The cost of such plugs might be as little as providing free orchestrations and other in-kind favors, or as much as a large cash stipend. Early proposals that the money flow should be reversed, that performers or performance venues should pay for the privilege of using a song, were met with derision. The exclusive right of public performance of musical compositions, added to the copyright law in 1897, languished in a state of neglect.

In 1912, however, a new form of entertainment was taking hold in New York. It would prompt some influential figures in musical circles to rethink the matter of performing rights. Variety called the new craze “midnight vaude.” Its promoters preferred the tonier sounding “cabaret.” Being “caterers rather than impresarios,” one writer later observed, “the proprietors developed the practice of taking whatever numbers they liked from current Broadway hits.” The first music business players to reimagine the possibilities of the public performance right were composers such as Victor Herbert, Raymond Hubbell, Louis A. Hirsch, and Glen McDonough, and Broadway-oriented publishers such as the Witmark Brothers and Max Dreyfus, who saw the cabarets as neither caterers nor impresarios, but as outright thieves.

France’s pioneering performing rights organization, SACEM, had recently set up a branch in New York City, and Hirsch—a forward-thinking 25-year-old boy wonder—had become one of its first American members. Using SACEM as its model, and with the legal guidance of the dean of the copyright bar, Nathan Burkan, the small coterie of Broadway denizens organized ASCAP to enforce the music performance right through the pooling of copyrights and issuance of blanket licenses. By its official launch in February 1914, the charter membership of 91 authors (i.e., lyricists) and composers included such crucial recruits as George M. Cohan, John Philip Sousa, Jerome Kern, and Tin Pan Alley’s recent breakout star, Irving Berlin. The nascent Society could credibly claim to represent a repertoire commercially essential to nearly any public place offering musical entertainment in the mid-1910s.

ASCAP’s strategy was to set licensing rates low; its initial fee schedule topped out at $15 per month for the largest cabarets, and 10 cents per year per seat for the other major target of its licensing efforts, movie theaters (the first motion picture palaces employing full orchestras were just then opening, but not even the humblest second-floor nickelodeon would think of showing a “silent” movie without musical accompaniment). “Anyone,” Burkan naively predicted, “would pay a small fee” for unlimited use of the ASCAP repertoire. It didn’t work out quite that way.

Opposition to the “Music Tax” was instant and massive. Imposing a charge for something that business owners were accustomed to using for free triggered strident rhetoric and threats of reprisal grossly disproportionate to the dismal little millage that ASCAP was trying to collect. ASCAP’s rather measly revenues were consumed by litigation expenses. Only after the Supreme Court’s landmark 1917 decision in Herbert v. Shanley Co., which established the principle that musical performances incidental to a commercial establishment’s main draw (such as food or a movie) violated the copyright owners’ exclusive public performance rights, did the tide begin to turn.

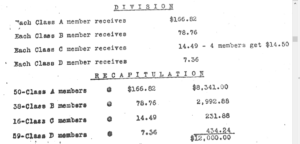

Seven years would pass before ASCAP was able to distribute performance royalties to its members for the first time, while maintaining an adequate reserve ($100,000) against continuing litigation and administrative expenses. For the first quarter of 1921, a grand total of $12,000 was available to be divvied up among 163 songwriter-members. (Another $12,000 was distributed to the publisher-members.) On April 5, 1921, a committee of 10 veteran songwriters (including Herbert, Hubbell, Hirsch, and McDonough) met to apply, for the first time, the mostly subjective classification criteria set out in the Society’s Articles of Association: (1) the number and nature of a member’s works; (2) the “popularity and vogue” of those works; (3) the length of time those works had been in the Society’s repertoire; and (4) “the prestige, reputation, qualifications, standing and service which such member has rendered to the Society.”

It was a difficult slog. ASCAP had required its early licenses to submit complete logs of all performances, but the mass of paper that had accumulated proved to be useless to the task at hand: “Try and figure out,” Hubbell wrote, “how many girls we’d have to hire to take care of the programs for the entire United States and how much money you’d have left to pay royalties.” Ultimately, their approach was one of you know it when you see it, relying on the good judgment of “honorable men” giving “time, patience, and study to the task.”

The four-tier classification they adopted gave considerable credit for longevity and prestige. Old-timers (who had sustained ASCAP during the fallow years) were rewarded, as were composers of high-brow music, even though their works had little public performance activity. The “A” classification, which came with a dividend of $166.82 (about $2,450 in current dollars), was bestowed generously on once-dominant, but by-then-declining Tin Pan Alley (Ernest Ball, Billy Jerome, Harry and Albert von Tilzer) and Broadway (Herbert, Cohan, Gustave Kerker, Silvio Hein) warhorses. The “B” class ($78.76) included well-regarded composers of orchestral concert music such as Harry T. Burleigh and Henry Hadley.

But the most interesting aspect of this first whack-up is its recognition of the rising generation that was just beginning to write the Great American Songbook. The “A’s” included Irving Berlin, Jerome Kern, Gus Kahn, Harry Ruby, and Buddy DeSylva; the “B’s” George Gershwin, Al Jolson, Al Dubin, Milton Ager, and Jack Yellen; Fred Alhert and Irving Caesar were “C’s” ($14.49); and Ira Gershwin and Vincent Youmans were “D’s” ($7.36). Other giants of the Great American Songbook era—Harold Arlen, Cole Porter, Richard Rodgers, Harry Warren, Hoagy Carmichael—were still a few years away from ASCAP membership.

The amounts available for distribution grew quickly over the next decade, as radio and sound-synchronized motion pictures created massive new outlets for the public performance of copyrighted music. Performing rights became the songwriter’s most important source of income and the popular songwriter was writing first and foremost for the professional performer, not the home musician.

The standards of the Great American Songbook are products of this new business paradigm. Songwriters were no longer subsistence piece workers prized solely for their conformity to established rules, or for their ability to crank out knockoffs of the latest hit, or to cater to the latest dance craze. The important songwriters of the Great American Songbook age were comparatively autonomous auteurs, free to make demands on the public, instead of kowtowing to its established preferences.

Great stuff Gary! Hope all’s well.

Terrific blog, Gary. I write about copyright and I used to (and soon will again) host a radio show about singer/songwriters. One question: How did the rise of BMI affect all of this?