CHARLIE IN THE HAREM

Charlie Chaplin’s films repr esented only a small fraction of the commerce being transacted in his name, image, and antics during the World War I era. Adventures of a Jazz Age Lawyer recounts how Chaplin’s lawyer, Nathan Burkan, chased down spurious Chaplin films that he considered “vulgar, suggestive, and obscene.”

esented only a small fraction of the commerce being transacted in his name, image, and antics during the World War I era. Adventures of a Jazz Age Lawyer recounts how Chaplin’s lawyer, Nathan Burkan, chased down spurious Chaplin films that he considered “vulgar, suggestive, and obscene.”

Professional Chaplin imitators were appearing onstage in every city. Competition among them was so keen that an ad for one touted, with no conscious irony, that “of all the imitations of Chas. Chaplin, Dedic Velde in ‘Chas. Chaplin’s Double’ stands out alone in his clever and original imitation.” The imitators were paying no compensation to the original, and Chaplin was paying them no mind. Syd Chaplin’s brainchild for capturing revenue from marketers and merchandisers―the “Charlie Chaplin Advertising Service Company”―was undercapitalized and lacked the resources needed to compete in what amounted to a worldwide game of whack-a-mole. And in May 1916, the court ruling allowing Essanay to distribute an adulterated version of Charlie Chaplin’s Burlesque on Carmen gave a green light to opportunists who were eager to cash in on Chaplinitis in the one medium where there had been, up until then, only one Charlie Chaplin: the moving pictures.

The fake Chaplin films first began popping up under the radar, in smaller cities, at second- and third-tier theaters that were thrilled to put the magical name “Chaplin” on their marquees for rentals of as little as $1.50 per day. The first wave included Charlie the Heart Thief, Charlie in the Trenches, and Musketeers of the Slums. These were apparently crude pastiches of Keystone and Essanay clips, culled from worn-out positive prints that were used to make new negatives, a venerable method of film piracy known as “duping.”

The distributors of the spurious pictures avoided publicity that might attract Chaplin’s attention. They used direct mail or, occasionally, a classified ad in a trade journal to promote their wares. Local exhibitors were not so circumspect. Their ads and press releases were as conspicuous as they were breezily and willfully misleading. “We have secured Charlie Chaplin’s latest gloom killer, Charlie the Heart Thief,” one theater announced in August 1916. “This is Charlie’s latest production and the funniest the $500,000 comedian has ever appeared in.”

After word of the fake Chaplin comedies reached Syd Chaplin’s ears, he approached Nathan Burkan about taking legal action to suppress them on a contingency-fee basis. Suspecting that any money judgment against the perpetrators would be uncollectible, Burkan prudently declined. Emboldened by Chaplin’s inaction, knockoff artists introduced a second generation of fakes which combined old Chaplin clips with new footage that featured Chaplin impersonators. The Fall of the Rummy-Nuffs, a comical take on the Russian revolution, had a Tramp-like character called “Chaplinsky.” Thumbing their noses at Chaplin, the distributors of Rummy-Nuffs booked it into New York City’s Crystal Hall theater on Union Square, a well-established Mecca for Chaplin fans with an all-Chaplin-all-the-time booking policy.

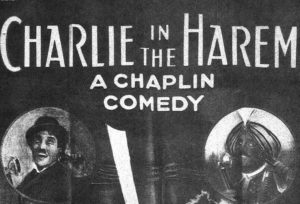

In the summer of 1917, the New Apollo Feature Company released Charlie Chaplin, a Son of the Gods and Charlie in the Harem. Using double exposure to embed authentic Chaplin images into locations and action completely alien to Chaplin’s original plot and mise-en-scène, these productions marked a technical leap forward in fakery. New Apollo made the mistake of offering these films to Sid Grauman’s Empress Theater in San Francisco, a venue Charlie had played in his vaudeville days. It was Grauman, one of Chaplin’s earliest admirers, who prodded Syd Chaplin into opening Charlie’s checkbook to put Burkan’s office on the trail of the fraudsters.

Son of the Gods features the Tramp in consort with a bevy of mermaids in Neptune’s underwater court. Charlie in the Harem is set in Turkey, where the Tramp meets “a couple of harem chickens out for a lark.” Disguised in drag as the lovely “Pearl of Persia,” he finagles his way into the Sultan’s palace, where he enchants both the Sultan and his brood with Charlie Chaplin imitations, only narrowly escaping death when his ruse is discovered. “No more likely situation could be offered this irrepressible comedian than the interior of a Turkish ménage,” one theater teased, “and Charlie does the situation full justice.”

A lobby poster for a spurious Charlie Chaplin film, 1917.

Posing as an exhibitor’s representative, Burkan was able to arrange a screening of the New Apollo films at the Rialto Theater in New York. “The effect created” by the composite scenes, he reported to Syd, was “bungling” and “does not do any credit to Charlie.” Burkan found the films, on the whole, “vulgar, suggestive, and obscene.”

Burkan tracked down the producers of more than a dozen fake Chaplin pictures. “It is a pity that we did not throttle this business at its very inception,” he told Syd. “They have come to regard this as a perfectly legitimate business.”

The defendants folded rather quickly, each readily giving up the names of others in the distribution chain and, unfortunately for posterity, turning over the offending films for destruction by United States Marshals. By October 1917, Burkan felt that “the principal offenders have been brought to book” and that the publicity from the cases would deter others, but he urged the Chaplins to keep up the effort. He wrote to Syd:

It will mean a great deal more work to suppress this widespread evil. I have seen quite a number of these fake Chaplins and the spectacles are offensive, debased and degrading. The people who witness these exhibitions leave the theater disgusted. Charlie owes it to himself and his admirers to prevent the further dishonest use of his name, fame, and reputation.

The Chaplins, cash-strapped at the time, were not disposed to invest in waging perpetual war against counterfeiters. Burkan had difficulty collecting his fee for the work he had already undertaken.

* * *

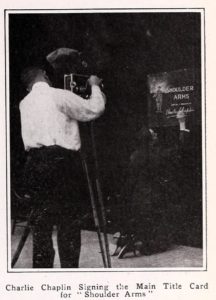

Burkan now understood that the extreme thrift for which Chaplin was already becoming legendary would require that he choose his legal battles strategically. He would have to erect a credible “Beware of the Dog” sign without a Rottweiler to back it up. He and the Chaplins cooked up a new plan to thwart counterfeiters: “The plan is simple,” Motion Picture News reported. “Chaplin is to be the first motion picture star to follow the universal practice of the brush artist by signing his works as proof of their authenticity.” It was not terribly effective, but it was cheap and it appealed to Charlie’s artistic vanity. Burkan was gradually learning how to manage a difficult client relationship.